Please don’t harm Ōwairaka’s trees for they are our tuakana (older siblings)

Honour the Maunga Patron Pouroto Ngaropo explains the Ōwairaka / Mt Albert tree situation in the context of a Te Ao Māori (Māori world view) perspective, and in the context of his own genealogical and spiritual relationship with the maunga. It is a ‘must read’ for anybody who wishes to gain a deeper understanding of the maunga tree situation.

A young totara growing under the protective cover of a condemned Holmes Oak on Ōwairaka.

Iramoko Marae, Te Tawera Hapū, Ngati Awa ki Te Awa o Te Atua fully believe that the life force in all things - in the universe, in the sky, in the earth, in nature, in the trees, in rocks, in birds, in fish, in all animals in the sea and on the land, in minerals, in water ways, in the mountains, in the geothermal vault line, in earthquakes, in islands, in the atmosphere, in space, in the stars, in the moon , in the sun and humans - all have one universal life force that binds all things together as one collective energy across space, time, location and dimensions.

Mauri is the life force that binds all things together. Everything is born of the earth, Papatūānuku, everything has the same life force, everything has the same spiritual universal energy that comes from the Creator - Io Te Waiora, the life-giver of all things. Mauri is the binding power that links all things together as one universal family across the universe.

Mauri

1. (noun) Life principle, life force, vital essence, special nature, a material symbol of a life principle, source of emotions - the essential quality and vitality of a being or entity. Also used for a physical object, individual, ecosystem or social group in which this essence is located.

Mauri is an energy that binds and animates all things in the physical world. Without mauri, mana cannot flow into a person or object. With mauri comes mana, being the pure energy that comes from the source of Creation, the fire and energy or the power source that provides life to all things contained within mana and tapu.

Mana

Mana refers to an extraordinary power, essence or presence. This applies to the energies and the presence of the natural world. There are degrees of mana and our experiences of it, and life seems to reach its fullness when mana comes into the world.

The most important mana comes from Te Kore – the realm beyond the world we can see, and sometimes thought to be the ‘ultimate reality’.

Tapu

Certain restrictions, disciplines and commitments have to take place if mana is to be expressed in physical form, such as in a person or object. The concepts of sacredness, restriction and disciplines fall under the term tapu. For example, mountains that were important to particular tribal groups were often tapu, and the activities that took place on these mountains were restricted.

The Flowing of Mana

The idea that mana can flow into the world through tapu and mauri underpinned most of Māori daily life. For example, sacred stones possessing mauri were placed in fishing nets, where they were able to attract fish. The stones were placed in bird snares for the same purpose. When fish arrived in the nets or birds in the snares, our ancestors saw something more than just the creatures before them – they saw energy within these physical forms. The harvest of fish was the arrival of Tangaroa, energy of the sea, which meant the arrival of mana.

Mauri stones were also used to prepare people who would receive mana. In the traditional whare wānanga (school of learning), small pebbles (whatu) were used in a student’s initiation ceremony. It was believed that when the student swallowed the pebbles, the mauri in them was taken into the stomach, establishing the conditions whereby mana in the form of knowledge and learning could come into the person. This is the reason behind Māori meditation practices, known as nohopuku (to dwell inwardly, in the stomach). Connected to this is knowing the taniwha - the guardians that look after and protect the life force of nature and keep the environment and people safe.

Taniwha

Taniwha are ferocious creatures or guardians, representing the life force (mauri) of a place in physical form. They were seen as a constant presence in mountains, ranges, hills, islands, oceans, waterways, ensuring that fish and other resources remain plentiful.

Tohunga (priests or spiritual navigator and other experts) were able to harness mauri and cause it to enter a boulder, a tree or a fish. This had such a powerful effect that the object seemed to take on a life of its own. There are many stories of trees moving against river currents and having a supernatural aspect, leading to a belief that these objects were taniwha.

Taniwha and chiefs

Taniwha were closely linked to the local chief of the hapū and marae of the area and or region, who was also known as a taniwha. The fertility of a region was seen as directly linked to the mana of that land and its chief, who would control the taniwha in the river. This is important in the concept of tangata whenua (people of the land). Only tangata whenua could control the mauri, and therefore the fertility, of their region.

The traditional Te Tawera Hapū World View and the traditional Māori world view

The cycle of the sun

The rising of the sun, the journey it makes across the sky, and its setting in the west is a cosmic mystery. Because this cycle is repeated every day, traditional Te Tawera ancestral thinking considered it the basic principle of the world. The sun represents the birth and growth of mana (power) in the world. The birth, rise and death of the sun came to be the primary model for all existence – all of life should in some way give expression to this pattern.

The orator’s role

When an orator rises to speak on a marae, he will often announce himself by saying:

Tihē mauriora (The breath, the energy of life)

Ki te whaiao, ki Te Ao Mārama (To the dawn light, to the world of light)

The words refer to a world constantly emerging from darkness into light.

The orator’s speech is considered to be a re-enactment of Tāne separating earth and sky, the means by which light came into the world. Tāne was the father of humankind. When he separated his parents, Papatūānuku (the earth mother) and Ranginui (the sky father), the sun was able to shine into the world that was created. If the orator’s words offer guidance and wisdom, he brings his audience out of the ‘night’ of conflict and into the ‘day’ of peace and resolution. This occurs when mana (a spiritual force) enters the person – just as the sun illuminates and brings forth the new day.

The genealogy of trees.

Understanding a World View

Looking back on history, we try to imagine the world view of the people of that time. Inevitably we see the past, or a traditional philosophy of life, through the lens of our own knowledge and experience. A people’s world view is complex and dynamic.

Te Tawera Hapū’s world view changed immediately after they arrived in Aotearoa. Encounter with European settlers brought further change. It is not possible to say that there is a single viewpoint in Māori culture today. The ideas set out here are only an attempt to understand the world view of our ancestors before Europeans arrived. That all things are connected and related so that all trees that come from the earth have the same life essence, as the water, as the ocean, as the mountain, as a stone and as people.

An Interconnected World

Genealogy of the trees (see diagram above)

Ranginui, Papatūānuku and offspring

Tangaroa’s descendants

The Battle of the Birds

In traditional Māori knowledge, as in many cultures, everything in the world is believed to be related. People, birds, fish, trees, weather patterns – they are all members of a cosmic family.

Whakapapa

This linking was explained in tātai (genealogies) and kōrero (stories), collectively termed whakapapa (meaning to make a foundation, to place in layers). Experts recited the whakapapa of people, birds, fish, trees and the weather to explain the relationships between all things and thus to place themselves within the world. This helped people to understand the world, and how to act within these relationships.

The Elements of Nature and their Families

The entire world was seen as a vast and complex whānau (family). In the Te Tawera story of creation, the earth and sky came together and gave birth to some 70 children, who eventually thrust apart their parents and populated the world. Each of the children became the the elements of nature, of a particular domain of the natural world. Their children and grandchildren then became ancestors in that domain. For example, Tangaroa, energy of the sea, had a child called Punga. Punga then had two children: Ikatere, who became the ancestor of the fish of the sea, and Tūtewehiwehi, who became the ancestor of the fish and amphibious lizards of inland waterways.

The Meaning of Whakapapa

Whakapapa (genealogies and stories) express our need for kinship with the world. They describe the relationships between humans and the rest of nature. In one tradition, some tribal groups and the fish of the sea claim descent from Tangaroa, the energy of the sea.

Whakapapa also explains the origins of animals, plants and features of the landscape. To tell a story about the origin of a bird, for example, is to invoke its true essence or character.

The Value of Oral Traditions

Although many of the stories are our historical narratives, they also have a practical function. They can pass on knowledge about the natural world, such as where to find kererū (New Zealand pigeons) and how to harvest them.

Although science is another way of understanding the natural world, the traditional principle of interconnectedness is still important and meaningful to Te Tawera. For example, the genealogy of a fish and sea animals makes it clear the kinship of people and other creatures. It also points out values that guide people’s interaction with other species, teaching respect and correct conduct.

Te Ao Māori in the Context of the Ōwairaka Tree Situation

Etymology

Mount Albert was named after Queen Victoria's consort, Prince Albert, following a petition in 1866 to the Superintendent of Auckland Province, Frederick Whitaker.

The main Māori name of the peak is Ōwairaka, which means 'Place of Wairaka'; she was the daughter of Toroa, the commander of one of the great voyaging canoes, Mātaatua. Wairaka is renowned for naming Whakatāne, a town in the Eastern Bay of Plenty where she saved the waka from drifting out to sea. She is depicted in the Statue of Wairaka located at Whakatāne Heads. Wairaka subsequently moved to Tamaki-Makaurau to avoid another arranged marriage and to look for her older brother Te Whakapoi and set up her own pā at Ōwairaka.

The Māori name Te Ahi-kā-a-Rakataura refers to the Tainui priest Rakataura aka Hape.

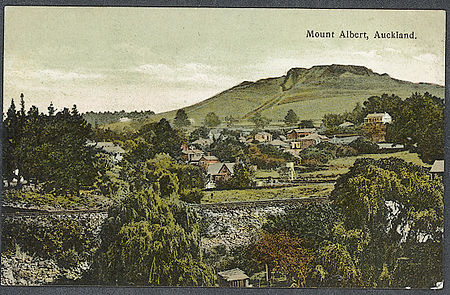

Ōwairaka / Mt Albert circa 1910.

The peak, in parkland at the southern end of the suburb, is 135 metres (443 ft) in height, and is one of the many extinct volcanic cones that dot the city of Auckland / Tāmaki Makaurau, all of which are part of the Auckland volcanic field. The age of the volcano is currently unknown. The peak was formerly the site of a Māori pā, a fortified settlement. Extensive quarrying has reduced the height of the scoria cone by about 15 metres (49 ft) and significantly altered its shape, but a few remnants of Māori earthworks such as terracing are still visible.

Current uses of the cone include several playing fields, an archery club and a 31,500 cubic metres (1,110,000 cu ft) water reservoir buried in a paddock on the mountain's southern side.

Treaty settlement

In the 2014 Treaty of Waitangi settlement between the Crown and the Ngā Mana Whenua o Tāmaki Makaurau collective of 13 Auckland iwi and hapū (also known as the Tāmaki Collective), ownership of Ōwairaka / Te Ahi-kā-a-Rakataura / Mount Albert was vested to the collective. However, the lands are held in trust for the benefit of Ngā Mana Whenua and the other people of Auckland. “The other people” includes Tangata Whenua who were excluded from that settlement. It is now co-governed by the collective and Auckland Council through the Tūpuna Maunga o Tāmaki Makaurau Authority in common benefit of the iwi "and all other people of Auckland". Half of the Authority’s members are iwi representatives, and half are Auckland Council representatives.

Under the Mana Rangatira of Te Tawera Hapū we are committed to ensuring the life force of the 345 trees are looked after and protected at Ōwairaka as this has an impact on the entire mauri and mana of the mountain and environmental system of Papatūānuku.

The current situation

We acknowledge and respect all the tribal histories of Ōwairaka. It’s not an issue of mana whenua for us, it’s about protecting the mana o te mauri of our tuakana the trees and to be a proactive supporter of kaitiakitanga to protect the land and our environment for future generations unborn.

Honour the Maunga, Iramoko Marae enter unique a unique partnership

Honour the Maunga has maintained an ongoing tree-saving presence at the maunga since November 2019 and its actions have helped safeguard around 2500 trees on other maunga administered by Tūpuna Maunga Authority.

Honour the Maunga Patrons Pouroto Ngaropo and Sir Harold Marshall.

The community group formed a relationship with Ngāti Awa ki Te Awa o te Atua - Te Tāwera Hapū - Iramoko Marae in late November 2019 and has deepened it through a series of gatherings and discussions on the maunga and at the hapu’s marae, near Matatā.

The partnership, which was formalised at the marae in July 2020, saw Honour the Maunga members accepted as uriwhanaunga (extended family). This accords them a number of rights, including being able to stay on the marae as whanau, and eventually to be buried in the marae’s urupā should they so wish.

Honour the Maunga’s representatives sit on various marae committees, including the Governance and Environment Runanga (councils), and its members provide additional expertise and support for a range of the marae’s activities.

I was honoured to beocme an Honour the Maunga Patron, alongside Sir Harold Marshall, continuing my active support of the group with cultural guidance, providing advice and participating in ongoing public discourse on the tree issue.

We are all working together to protect Ōwairaka and her flora and fauna in a way that gives life to the Treaty of Waitangi. In doing so, we are acknowledging and protecting the mauri and histories of my hapu’s ancestress Wairaka, from whom the maunga was named, and those of the many others who have been here over the centuries.

The high-born chieftainess Wairaka established her mana and mauri over the maunga around 850 years ago and her wairua (spirit) flows strongly through the maunga and surrounds to this very day.

Iramoko Marae and Honour the Maunga both affirm that we do not claim any ownership of the maunga’s land. However, both groups have our own deeply held spiritual relationships with it.

Our partnership and our respective goals for the maunga are based on Te Ao Māori – the Māori world-view of the environment, which acknowledges the interconnectedness and inter-relationships between all living and non-living things.

Honour the Maunga and Iramoko Marae’s strategic plan reflects this shared view, undertaking to embody Mana Atua / Spiritual connection – with the land (whenua), with ancestors (tūpuna) and with people (tangata).

We both acknowledge the Ōwairaka situation has been fraught at times within the Auckland community but our partnership is designed to role-model a positive Treaty partnership that celebrates unity while respecting each other’s differences.

Ōwairaka’s aquifer flows out to Western Springs, another site of historic importance to Te Tawera Hapū, Iramoko Marae. Felling all of the maunga’s exotic trees and the associated herbicide usage will increase erosion and toxic run-off into the aquifer.

The fate of Ōwairaka’s trees is unclear at present, following a Judicial Review decision that has cleared the way for the trees to be felled. However, the Judicial Review applicants are appealing the decision and have applied to the High Court for an injunction to protect the trees from any harm until the appeal decision is delivered. The injunction application will be heard in the Auckland High Court on 10 February 2020.

Even should the Judicial Review appeal outcome or other events result in Ōwairaka’s trees being protected, or removed, there is a shared desire for Iramoko Marae and Honour the Maunga to continue working together on tree-saving, environmental and educational work, as well as to work together in supporting the marae to further revive Māori cultural practices and tikanga.

PROTECT THE TREES ON WAIRAKA FOR THEY ARE OUR TUAKANA.

References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount Albert (New Zealand).

^ a b Reed, A. W. (2010). Peter Dowling (ed.). Place Names of New Zealand. Rosedale, North Shore: Raupo. p. 255. ISBN 9780143204107.

^ Dunsford, Deborah. "Wairaka, heroine of her time". Mt Albert Inc. Mt Albert Historical Society. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

^ "Walking About: Pīta Turei, Te Wai o Rakataura". Our Auckland. Auckland Council. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

^ "Ngā Mana Whenua o Tāmaki Makaurau Collective Redress Act 2014". New Zealand Legislation. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

^ "Tūpuna Maunga o Tāmaki Makaurau Authority". Auckland Council. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ "Changes to vehicle access on Tūpuna Maunga". Auckland Council. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ a b "Ōwairaka / Mount Albert Trees". waateanews.com. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

^ "Meet the activists trying to stop native trees being planted on Mt Albert". Newshub. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ "Ōwairaka/Mt Albert tree war heads to High Court as Auckland citizens take on Tūpuna Maunga Authority". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

^ "Tūpuna Maunga Authority wins court battle in Ōwairaka/Mt Albert tree war". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide. Hayward, B.W.; Auckland University Press, 2019, 335 pp. ISBN 0-582-71784-1.

References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount Albert (New Zealand).

^ a b Reed, A. W. (2010). Peter Dowling (ed.). Place Names of New Zealand. Rosedale, North Shore: Raupo. p. 255. ISBN 9780143204107.

^ Dunsford, Deborah. "Wairaka, heroine of her time". Mt Albert Inc. Mt Albert Historical Society. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

^ "Walking About: Pīta Turei, Te Wai o Rakataura". Our Auckland. Auckland Council. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

^ "Ngā Mana Whenua o Tāmaki Makaurau Collective Redress Act 2014". New Zealand Legislation. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

^ "Tūpuna Maunga o Tāmaki Makaurau Authority". Auckland Council. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ "Changes to vehicle access on Tūpuna Maunga". Auckland Council. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ a b "Ōwairaka / Mount Albert Trees". waateanews.com. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

^ "Meet the activists trying to stop native trees being planted on Mt Albert". Newshub. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

^ "Ōwairaka/Mt Albert tree war heads to High Court as Auckland citizens take on Tūpuna Maunga Authority". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

^ "Tūpuna Maunga Authority wins court battle in Ōwairaka/Mt Albert tree war". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide. Hayward, B.W.; Auckland University Press, 2019, 335 pp. ISBN 0-582-71784-1.